Brain Injury Association of Pennsylvania’s 2022 Conference

Penn Square is pictured on an early Sunday morning from my room at the Lancaster Marriott Hotel.

Penn Square is pictured on an early Sunday morning from my room at the Lancaster Marriott Hotel.

device

(With apologies to William Carlos Williams)

Story, photos by Sharon Kozden

On an otherwise ordinary weekend in 2012, my father walked a short distance on a treadmill before failing miserably his cardiac stress test.

He was subsequently hospitalized and scheduled for double-bypass surgery on Monday with a cardiothoracic surgeon who shared his Polish ancestry. That weekend, however, Dr. Ray Singer (of Jewish descent) was the attending surgeon.

I remember sitting in a sterile hospital room with my dad—he of the expert potato pancake-making skills—and with my latke-eating and then-presumed life partner, never realizing it would be the final conversation with my father as I’d always known him. Our lives were about to be drastically and irrevocably altered.

The chat was a remarkable one; I am comforted by my memories of it. So hopeful and loving–a literal heart-to-heart of a lifetime. My dad told me I had a good man, a keeper. My then-keeper eased my father’s concerns about his impending surgery with a fraternal and personal share. I cry now, unabashedly and unapologetically, while writing this reminiscence.

I can’t really recall what next occurred, the disturbance happened rather suddenly. I do know a nurse had entered the room, interrupting our secret society, our revelatory reverie.

“How are you feeling, Mr. Kozden?” And, “Do you have any chest pain?”

In typical Andy-Daddy fashion, my father minimized his actual experience. He admitted that, well, maybe he was feeling a little something. Chaos ensued. I moved out of the way; my dad was being stat-wheeled to the operating room.

I stood there, numb and terrified. Nothing was going according to plan. Monday was the scheduled DOS (date of surgery). And where was the Pole? Dr. Singer was now the surgeon about to crack open my father’s sternum (or however he intended to access the damaged organ).

I turned to my partner, asking if my dad would soon be frying up latkes and possibly even, pending surgical outcome, converting from Catholicism to Judaism. It was a wan attempt to suppress my own fear with humor. Having that ancestral commonality between my father and the man who would hold his life in his hands, I later realized, served to temper my worried mind, hence my concern over the doctor switch.

Good news soon followed. The double-bypass surgery resulted in stabilization of coronary-artery blockages. The caveat disclosure, however, was dire. My father stroked suddenly while hooked up to the chilling machine and coded for a dizzying length of time. A brain starved for oxygen.

Dr. Ray later informed my family in the hospital waiting room that our patriarch had suffered an anoxic brain injury and remained unresponsive. While my daddy lingered comatose and intubated in a hospital bed, the five of us were forced to entertain having the talk no family wants to imagine. The plug-pulling discussion. I shudder to type these words.

After the fact, Dr. Ray confided to me he’d thought of us all in the waiting room–that interminable and nearly intolerable time lag. Throughout the actual surgery, as we paced and fretted nearby, we’d never known how valiantly and persistently one man (and with his team) massaged my father’s heart to resuscitation.

At some point during my dad’s post-surgical unresponsiveness, I was advised to return to work and life. I would be called instantly with even the slightest of condition changes. Consequently, I proceeded to take up space in an office cubicle, although I can’t say I actually worked.

When the notification call came, Dr. Ray was on the line. “Sharon, your father is responding to signals.” I alternately screamed, cried and laughed, grabbed my belongings and hightailed it to the hospital, where I implored my dad to blink if he knew me. He blinked. I asked my dad if he knew me. Through the intubation tube snaking into his trachea, he mouthed my name on request. S-H-A-R-O-N.

And with that mouthing, what would become for my father a seven-year battle with brain injury commenced. It was the anoxic insult he would endure until he died. Whatever had been normal was gone forever. New normal would be a multi-offensive experience I wouldn’t wish on anyone’s proverbial enemy.

My aged mother quickly found herself tasked with nursing duties–straight-catheterization (size 14 French) three or more times a day because my dad couldn’t void on his own post-operatively. His driver’s license was revoked after he was tested (and failed) by someone from Allentown’s Good Shepherd Home. He couldn’t be trusted to heat a can of soup on a stove after impairment to his short-term memory. He angered easily and asked the same questions repeatedly. Word-finding was a struggle. Asked his age, he was 38, not 86. I had to learn to meet him where he was and cease with my correcting. If George Washington was President that year, so be it.

My dad began developing urinary tract infections on the regular and seemed to exist cyclically between brewing bacterial invasions to ones full-blown. All were accompanied by significantly distressing symptoms, namely confusion and balance issues, which prompted blood draws to confirm the expected diagnosis. A course of bacteria-slaying antibiotics was then prescribed until the entire frustrating cycle would begin anew. This is the state my dad existed in because no one wanted to contemplate or even admit the unthinkable act of admitting him to a memory-care unit in a nursing home. A man’s home is his castle, right?

With sadness, resignation and at long last, we relinquished our collective denial and concluded that my then 90-year-old mom faking some nursing degree was in no one’s best interest. Letting go of said denial—after many exhausting attempts to keep the status quo rather than remove my father from his home—was emotionally brutal. But when repeat short-term rehabs stints following these infections began to trump actual time at home, something had to be done. And with no other available option, my dad took up permanent residence at the Phoebe Home in Allentown.

Thing is that he never called it home. Whenever I would return him to the place after outings to doctors’ visits or other excursions, he would ask me not to take him back to “work.” Faulty word-finding. His brain injury also prevented him from swallowing normally. He would aspirate food or fluid into his lungs, then develop aspiration pneumonia. I remember a nurse telling me that we humans can even draw in our own saliva. Sounds like time for eyes-on round-the-clock care to me.

My dad’s mortal coil met its final affront when a pneumonia infection turned septic, setting off a systemic inflammatory immune response from which he could not rise above. He would, though, come to rise above (so to speak) after second-stage Severe Sepsis set in, which led to Septic Shock, the final phase before death.

One day, the head nurse—during a random shift on some seemingly arbitrary day—called me to say she’d just left my father’s room and was shaking. She related to me their brief conversation. “Andrew, are you ready to meet your Maker?” “Yes,” came the answer. “I’ve had a good life,” my dad shared. “But no one should have to live this way.” My father was then hospitalized until his oxygen saturation level sank dangerously low. He was transferred to the hospice floor, where he was lovingly and expertly cared for until his death on February 7, 2019.

My long-standing interest in “all things brain” predates my father’s passing by nearly a decade. While majoring in English, I was a member of the Neuroscience Club at Cedar Crest College, regularly attended Lehigh Valley Hospital’s Mini Medical School and read anything and everything I could find related to neuroscience. I even wrote poetry using words such as amygdala and neuron.

Had I downtime during the years I cared for my father while commuting and working full time, navigating a relationship and more, I may’ve discovered just how many helpful resources were available. Wanting to know more about such opportunities (albeit posthumously), I signed up to attend the Brain Injury Association of Pennsylvania‘s Annual Conference, a three-day event held at the Lancaster Marriott and Convention Center, circa summertime 2022. Attending the conference was a natural next step in the pursuit of learning more about my dad’s illness, a veritable no-brainer.

My dual roles as Medical Power of Attorney and primary caregiver for my father lasted seven long years as he battled brain injury. I ferried him regularly from Center Valley to specialists’ appointments at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, never realizing just how demanding and exhausting is the carer’s role. We’re so deep in the weeds on the daily, dealing with emergent issues that, with disease progression, increase in frequency and complexity, there’s little reflection time.

We motor on, handling emergency department visits, fielding calls from family members detailing sudden onset of frightening symptoms and more. Our shoulders become weighted with responsibility and from making critical decisions on the fly. We carers also often work full-time jobs, navigate romantic and familial relationships, attend to domestic duties and other obligations.

“Celebrating Connections and Collaborations in Brain Injury Rehabilitation” was the conference theme. I registered for many available lectures and presentations but still found time to snap pictures aplenty, meet and greet other survivors and listen to their very different (yet similar) stories. I also chatted with vendors, keynote speakers, family members and caregivers of injured loved ones. So many connections made. So much awareness gained. Read on for highlights from my journalistic journey in Lancaster, then check out my photo recap following this article!

It was a hot Saturday afternoon when I arrived and checked into the Lancaster Marriott at Penn Square. I’d left my brood of three back in Gladwyne, having thrown together a bunch of items I anticipated needing. I never call what I do packing. More like tossing a salad of overnighting ingredients haphazardly and hoping for a semi-decent outcome.

By the way, the Lancaster Marriott is one very nice hotel and adjacent conference center. My room was modern, neat, clean and orderly and had a lovely view of the city, where I saw nary a horse nor buggy.

Me being me, I wanted to tick off much more than I could accomplish on an always over-arching To-Do list. After years of struggling, I’ve learned to draft said lists then halve their content. I’ve further mastered the art of being okay with doing less, accepting that days usually mange to get away.

Time management is an oxymoron. Whether I was selecting a featured presentation to attend, enjoying one of the three provided daily meals or engaging in evening socializing, I paced myself and only did what I was comfortable doing. The conference actually reinforced such self-care measures even for someone without a serious brain injury. Overwhelmed? Take a break. Overpeopled? Cue solitary time. My introverted self sends thanks to BIAPA!

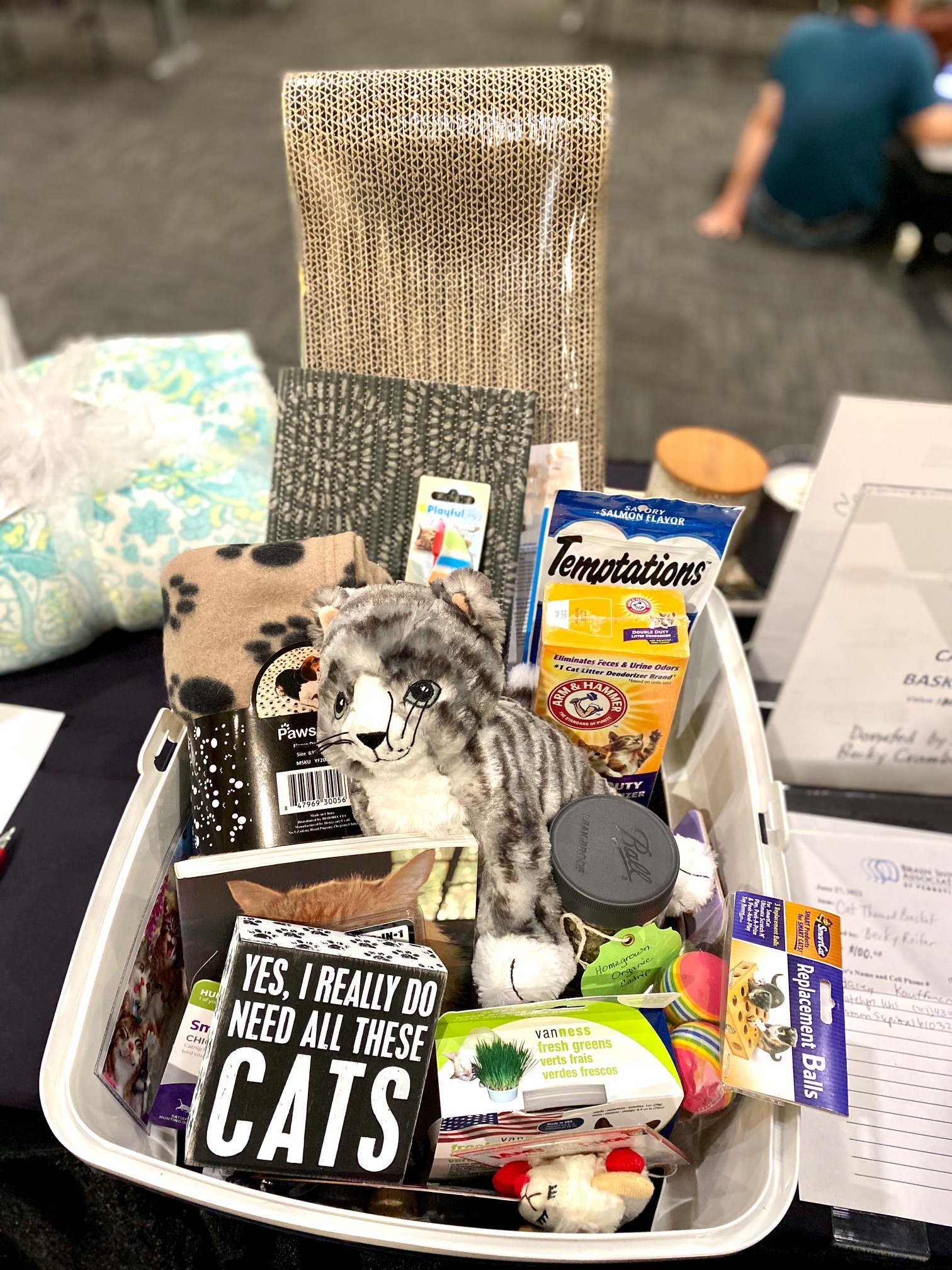

I located the silent auction area with its multiple rows of tables laden with impressive bid items. It’s worth pointing out that monies generated by the Silent Auction benefitted a scholarship fund enabling brain-injury survivors and caregivers to attend the conference. Exactly the folks who needed to be there.

One day, I hope to use this piece as catalyst for a book detailing my experiences while caring for my dad. Until then, I avail myself of publications and other resources such as BIAPA’s exceptional yearly conference to better learn that which my beloved father confronted during his seven-year tenure as a victim of circumstance–his “seven-year bitch” of a battle.

My overall takeaway observation of the conference was noting how very few affected attendees exhibited any why-me victimization in either word, behavior or attitude. That alone was worth the price of admission, which and thanks to my hosts’ generosity, I was exempt from.

I shed tears frequently, watching award recipients receive accolades, hearing specifics of caregivers’ and survivors’ stories and realizing just how many individuals give of themselves in order that others may learn to cope with challenging situations. Education and awareness. Care and compassion. And hope. Above all, hope. Hope always for that better quality of life through the connections and collective collaborations of those who innately understand we are all our brothers’ keepers “walking each other home.”

Side Note: One-week post-conference, I was in Philadelphia covering a 4th of July event, when the call came that my 95-year-old mother had been hospitalized. At the time, we did not know it was the beginning of her end. I carried on as best I could for the second half of 2022, my time divided between the job that paid my bills and my mom’s care. She died on January 17, 2023, and I am only now able to return to my writing as I newly navigate my earthly existence without a living parent–an indescribable albeit surreal time.

I am now writing again. My parents were always my biggest supporters and encouragers. For them and for myself, I introduce here a new iteration of my writerly self–a woman hoping to write herself home. And speaking of hope …

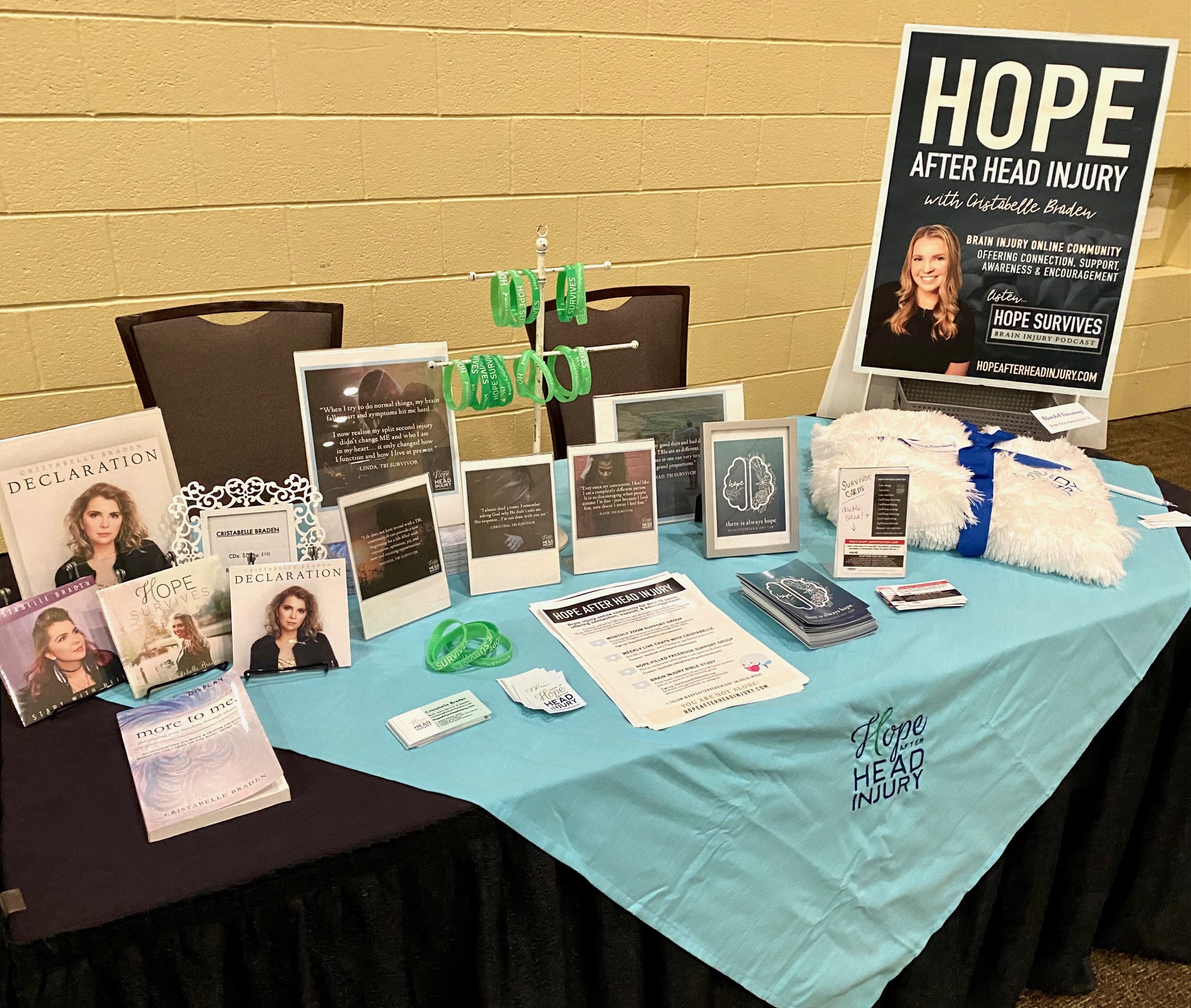

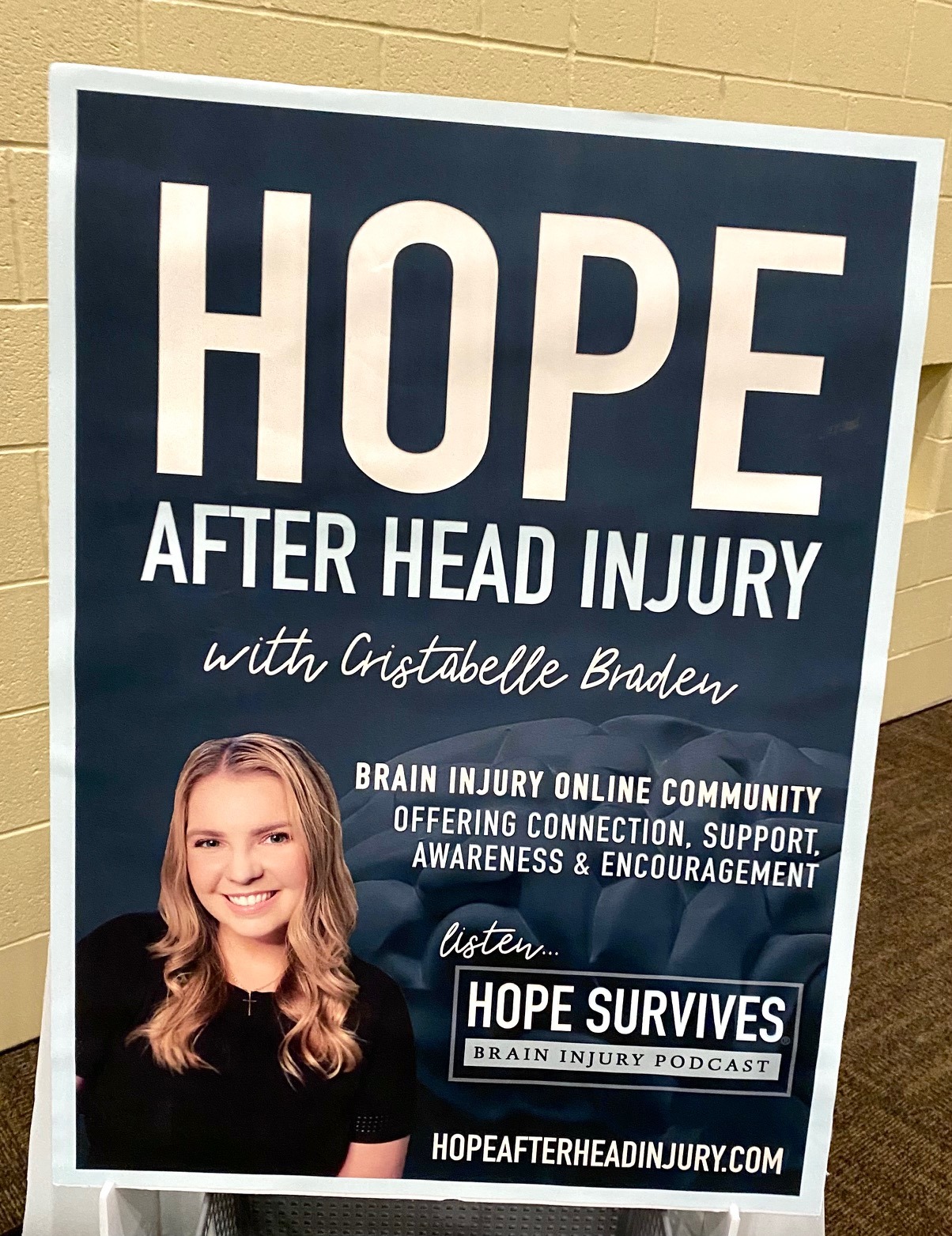

One of the conference’s keynote speakers–a singer/songwriter and national advocate for brain injury and founder of Hope After Head Injury–Christabelle Braden summarized survivors’ hope best in her song lyrics. To wit:

WE’RE GONNA MAKE IT(Cristabelle Braden 2017)

Twists and turns are a part of lifeBut when they burn, do we stay and fight?I don’t know what the future holdsBut I know there’s more than what I’ve been toldThe days are hard, and the nights are longBut fear won’t win when the love is strongYou’re not alone, walk right next to meThe little steps lead to victoryNothing can rain on our paradeNo matter what other people sayThey don’t know what you’re going throughDon’t know the hope that’s inside of youWe will fight through the darkest nightWe will rise with the morning lightWe will find the beauty in our scars

For more information and conference details, please visit the website @biapa.org

Gorgeous blooms in hanging baskets grace the Penn Square Clock donated by Chip and Chad Snyder to the City of Lancaster in 2016.

Gorgeous blooms in hanging baskets grace the Penn Square Clock donated by Chip and Chad Snyder to the City of Lancaster in 2016.

Roost on this: Lancaster Central Market is the country’s oldest continuously operated public Farmers’ Market–since 1730.

Roost on this: Lancaster Central Market is the country’s oldest continuously operated public Farmers’ Market–since 1730.

Music for Everyone (MFE) is a non-profit organization that unites communities through music with its “Keys for the City” initiative. I tinkled these rosy ivories during a stroll around Penn Square.

Music for Everyone (MFE) is a non-profit organization that unites communities through music with its “Keys for the City” initiative. I tinkled these rosy ivories during a stroll around Penn Square.

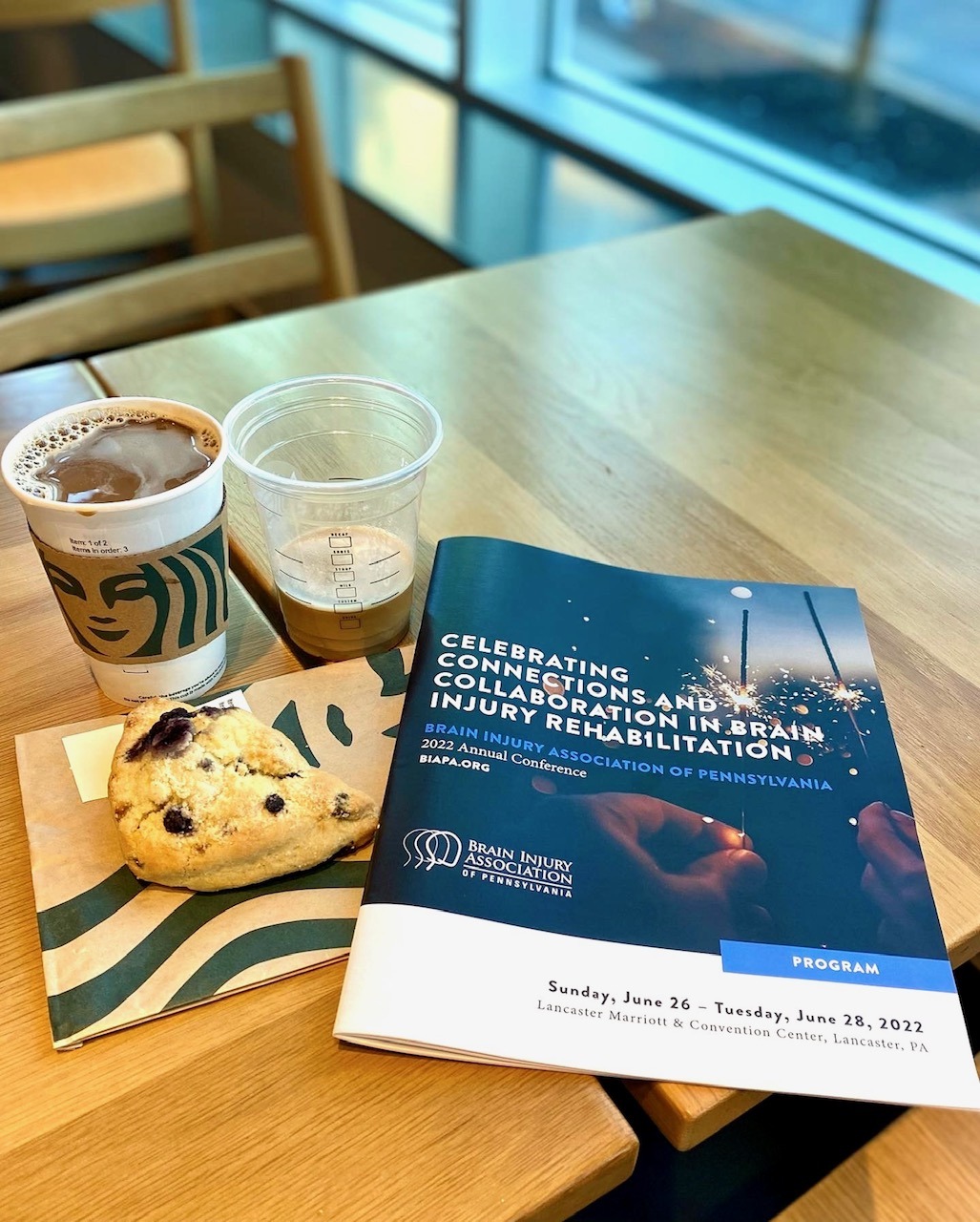

I really enjoyed my early mornings spent writing and program perusing at the North Queen Street Starbucks location, where I sampled my very first Nitro Cold Brew with Vanilla Sweet Cream, becoming 100% hooked and a lifer.

I really enjoyed my early mornings spent writing and program perusing at the North Queen Street Starbucks location, where I sampled my very first Nitro Cold Brew with Vanilla Sweet Cream, becoming 100% hooked and a lifer.

Lancaster Marriott at Penn Square did not disappoint in any way. This persnickety traveler highly recommends a stay here.

Lancaster Marriott at Penn Square did not disappoint in any way. This persnickety traveler highly recommends a stay here.

Calming blue hues, plenty of natural light, high ceilings, marble- and ceramic flooring and a pleasing, cosmopolitan seating arrangement create an inviting, spacious lobby area.

Calming blue hues, plenty of natural light, high ceilings, marble- and ceramic flooring and a pleasing, cosmopolitan seating arrangement create an inviting, spacious lobby area.

Modern decor and grand scale make for stately elegance. The Lancaster County Convention Center is merged with Lancaster Marriott at Penn Square.

Modern decor and grand scale make for stately elegance. The Lancaster County Convention Center is merged with Lancaster Marriott at Penn Square.

An abundance of natural light infuses the area near the entrance to Freedom Hall–the main exhibition space inside the Convention Center that boasts seating for 6,500 people.

An abundance of natural light infuses the area near the entrance to Freedom Hall–the main exhibition space inside the Convention Center that boasts seating for 6,500 people.

BIAPA’s signature blue and white color scheme and logo are represented by a directional sign and a welcoming balloon stand.

BIAPA’s signature blue and white color scheme and logo are represented by a directional sign and a welcoming balloon stand.

I arrived at this very spot after much planning, energy, time and effort and am ready for what BIAPA has to teach me.

Read the plaque on the actual incorporated brick wall of the 1804 Montgomery House–the mansion built for prominent local attorney William Montgomery.

Read the plaque on the actual incorporated brick wall of the 1804 Montgomery House–the mansion built for prominent local attorney William Montgomery.

Let the writing begin … at a most excellent workspace and writer’s station.

Let the writing begin … at a most excellent workspace and writer’s station.

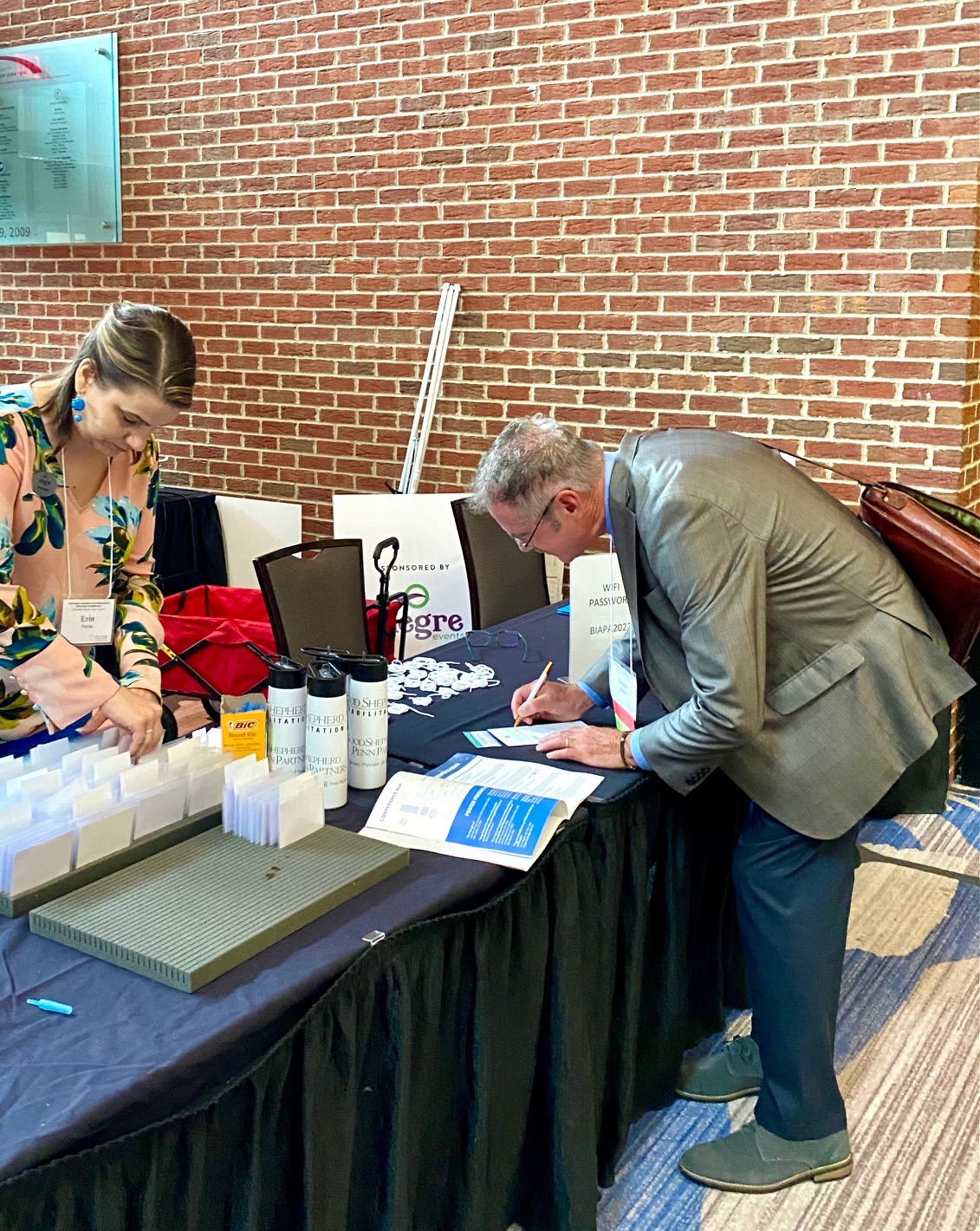

The conference check-in station was a hub of activity. Neuropsychologist Dr. Drew Nagale, a conference keynote speaker (June 26th) signs in.

The conference check-in station was a hub of activity. Neuropsychologist Dr. Drew Nagale, a conference keynote speaker (June 26th) signs in.

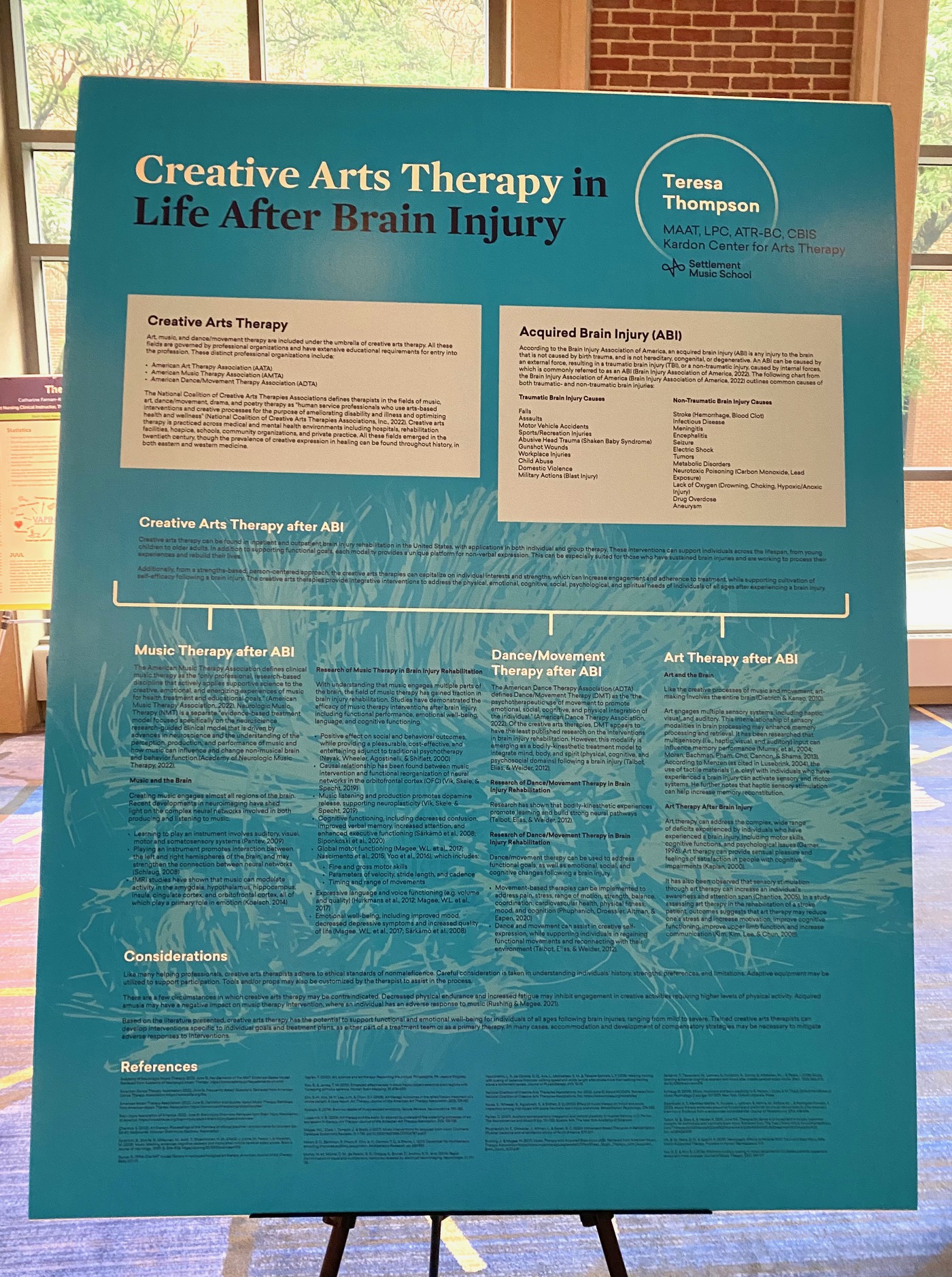

As one who doesn’t have a non-creative bone in my body, I was drawn to this board presentation from Teresa Thompson at Philadelphia’s Kardon Center for Creative Arts Therapy, which maintains that “music, dance and creative expression have the power to heal.”

As one who doesn’t have a non-creative bone in my body, I was drawn to this board presentation from Teresa Thompson at Philadelphia’s Kardon Center for Creative Arts Therapy, which maintains that “music, dance and creative expression have the power to heal.”

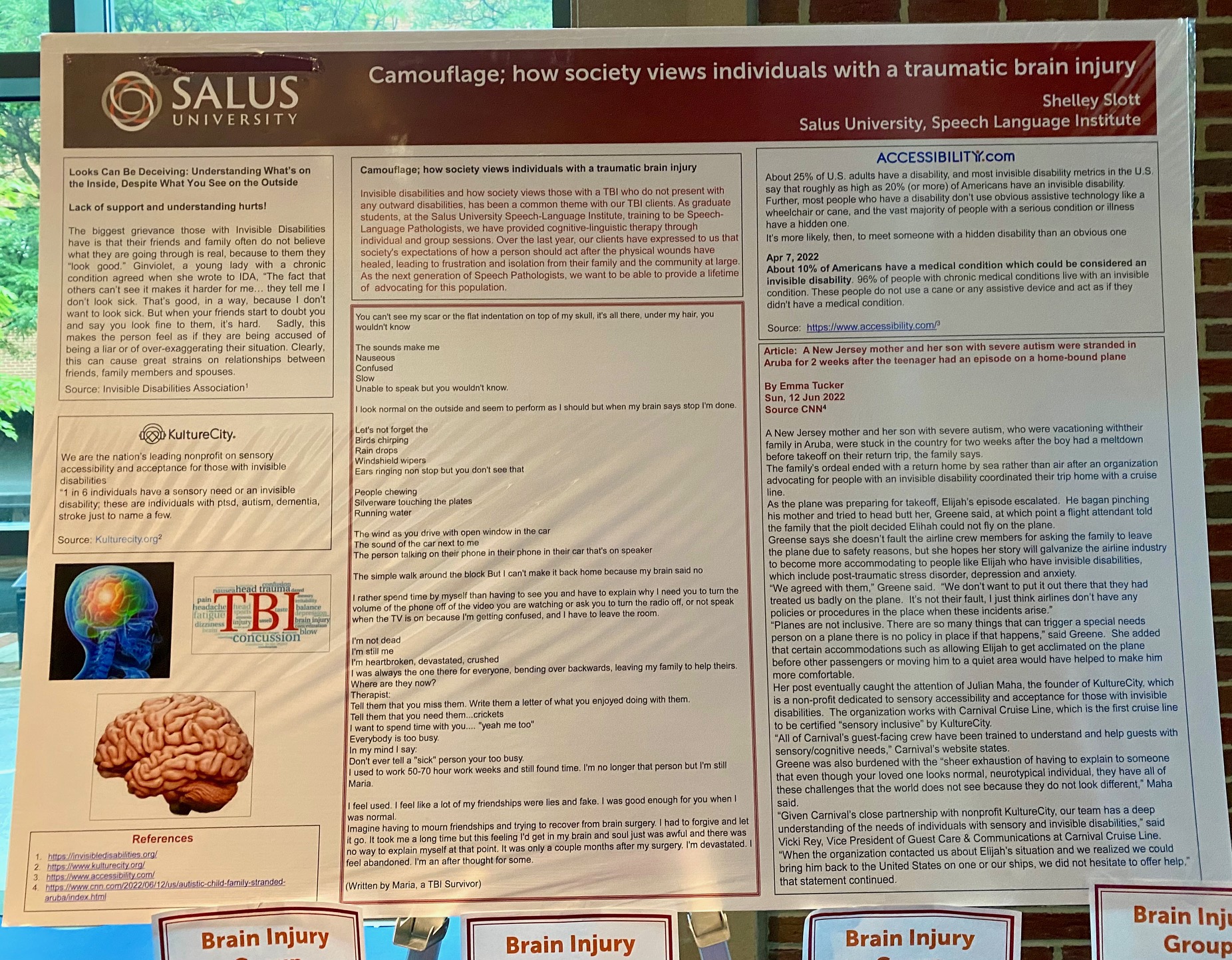

Another poster-board that caught my eye was this informative and educational presentation from Salus University‘s Speech-Language Institute.

Another poster-board that caught my eye was this informative and educational presentation from Salus University‘s Speech-Language Institute.

Thanks, Good Shepherd Rehab, for encouraging hydration and for all of the wonderful work you do.

From Left, Sharon Kozden poses with her host and Conference Coordinator Christine Schneider.

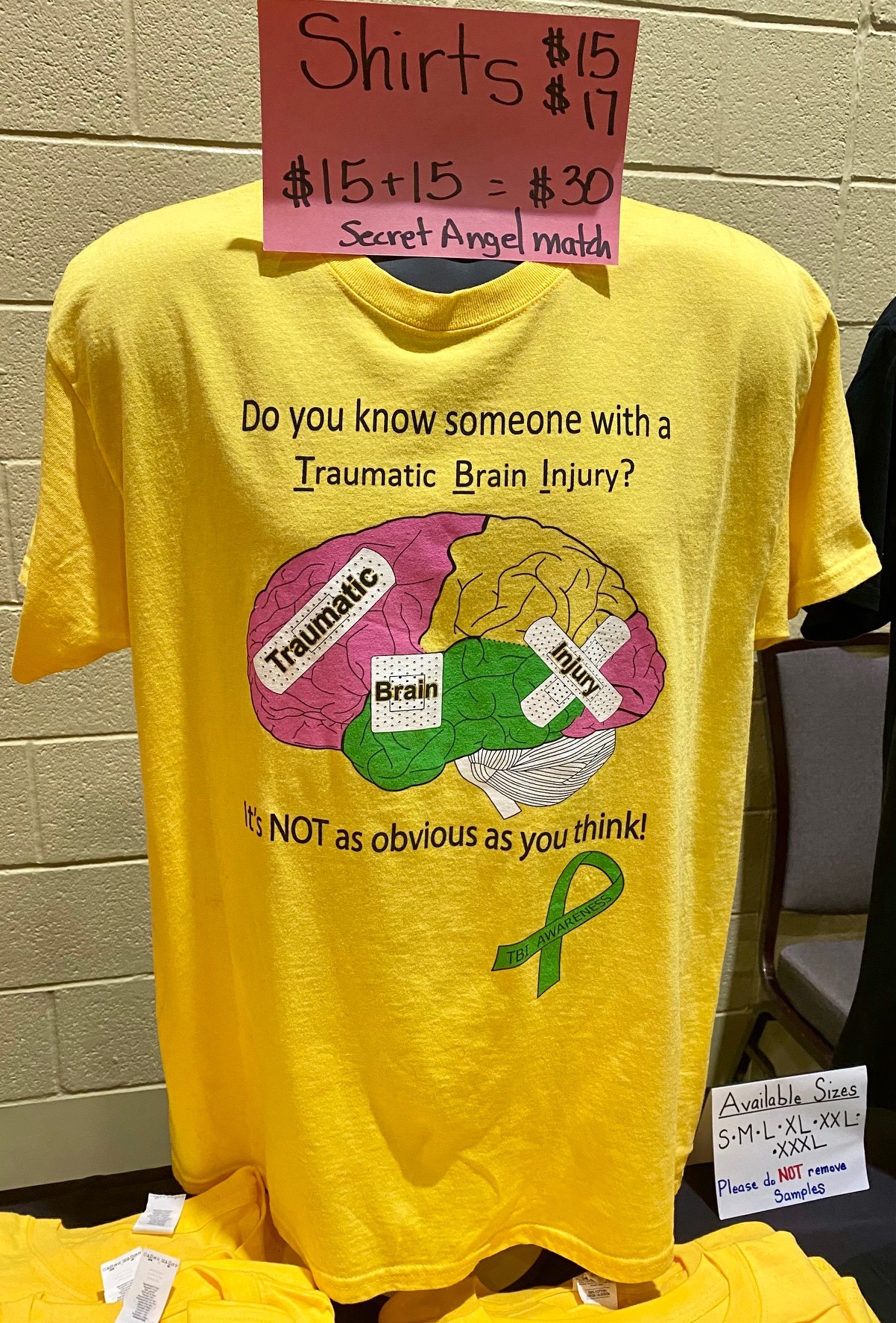

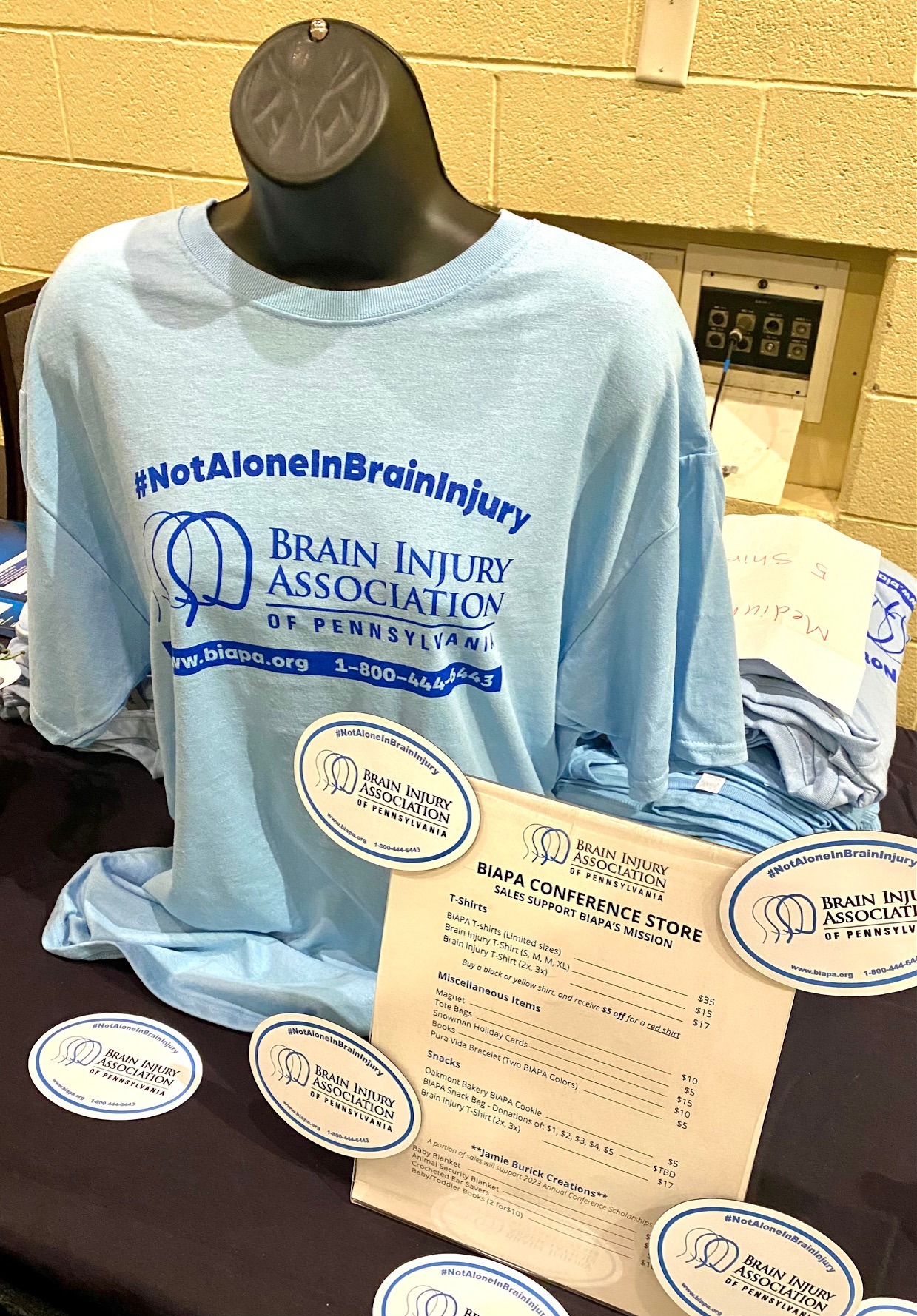

There was plenty of merch to get the word out about the essential and valuable BIAPA.

There was plenty of merch to get the word out about the essential and valuable BIAPA.

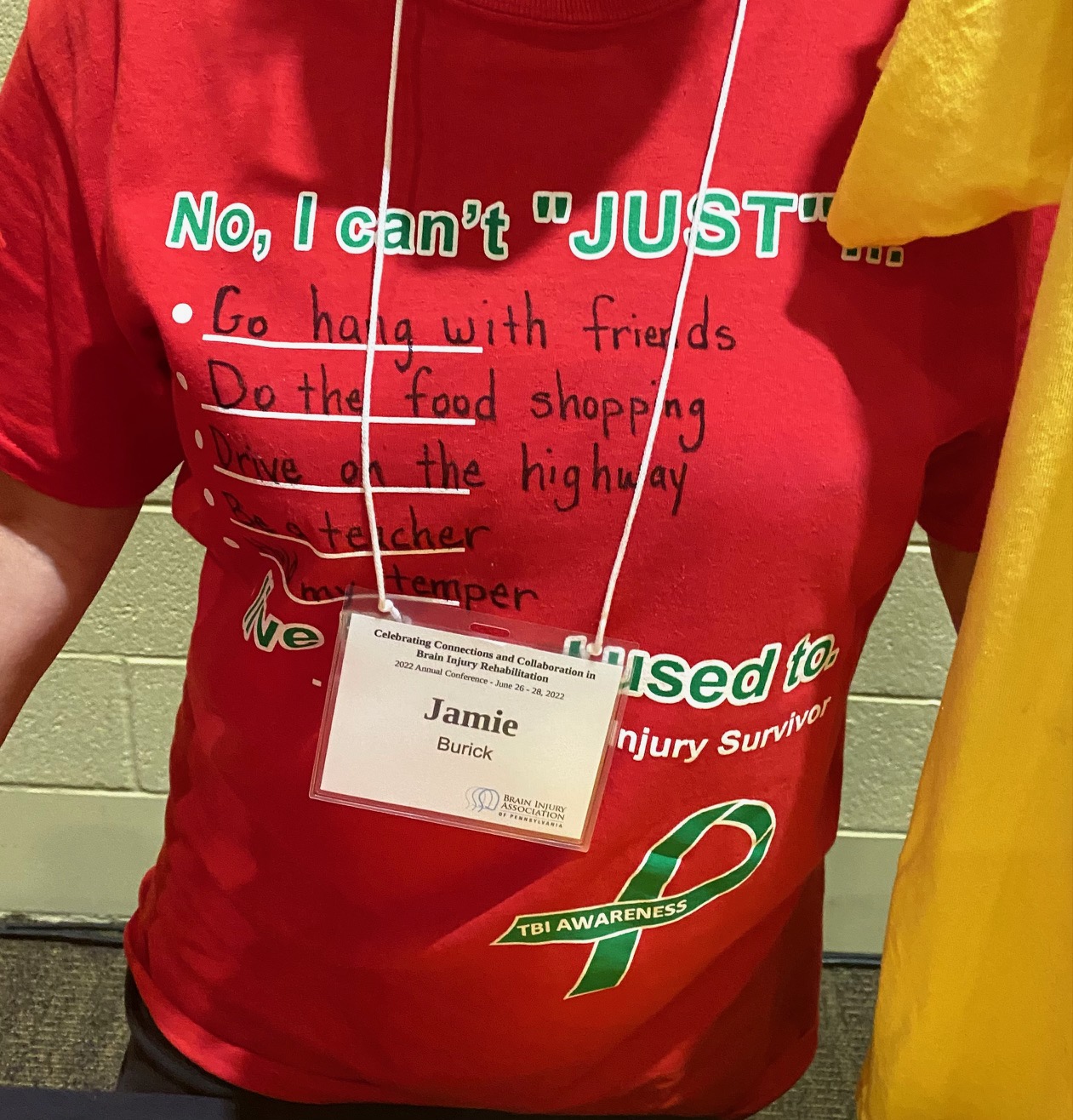

Awareness is key, and these well-designed tees get the word out.

Awareness is key, and these well-designed tees get the word out.

Jamie Burick poses with the tee-shirts she created, including this personalized fill-in-the-blank winner.

Jamie Burick poses with the tee-shirts she created, including this personalized fill-in-the-blank winner.

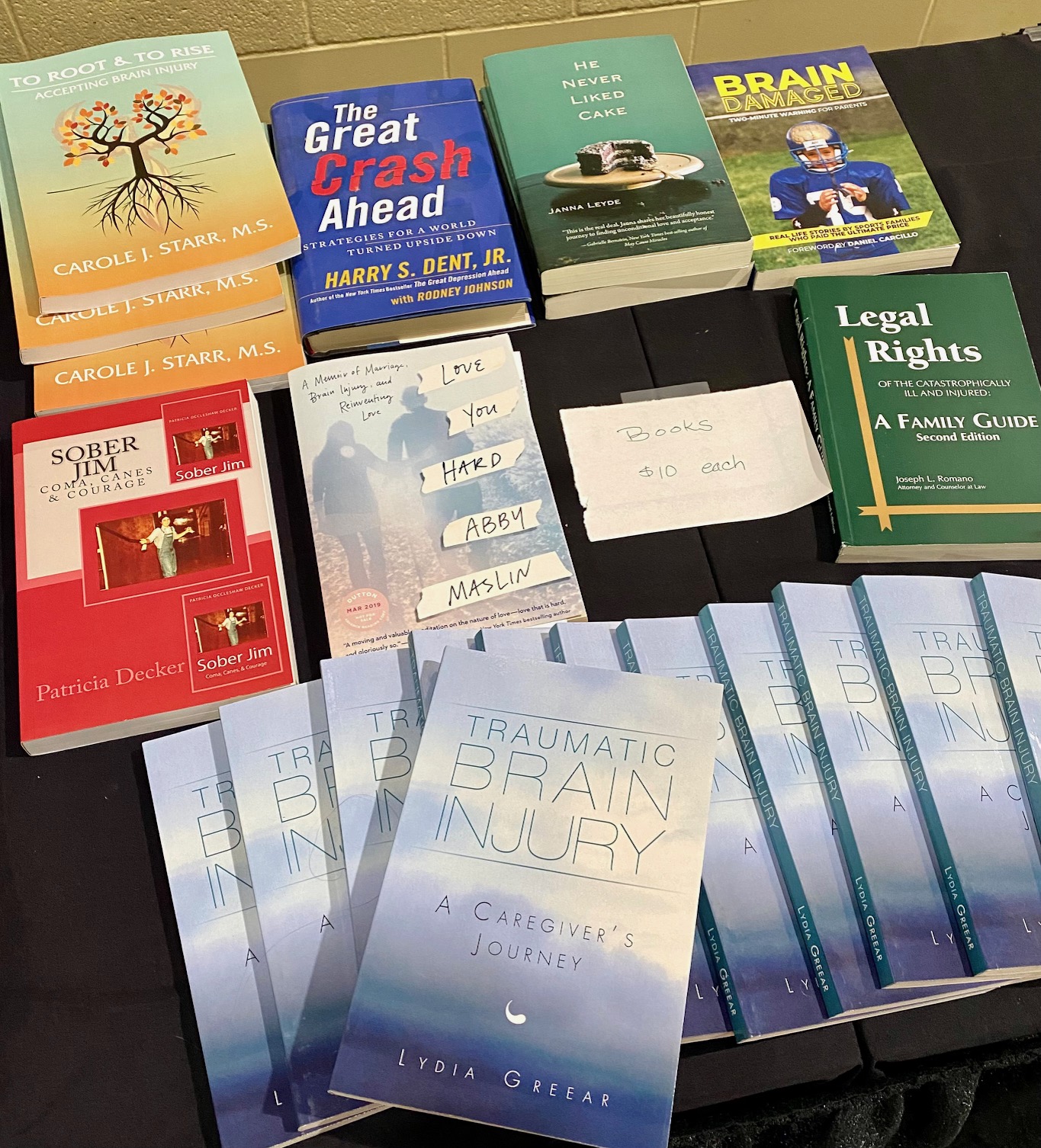

Books explain the journey involved for those with brain injuries as well as those who care for and love them.

Books explain the journey involved for those with brain injuries as well as those who care for and love them.

This time the message comes via cookie, not bottle.

This time the message comes via cookie, not bottle.

Bakery-made cookies do not crumble.

Bakery-made cookies do not crumble.

Silent Auction items fill multiple tables.

Silent Auction items fill multiple tables.

A gift basket because who doesn’t love a care package?

A gift basket because who doesn’t love a care package?

There is plenty of feline fun in this litter box.

There is plenty of feline fun in this litter box.

I spy a lot of useful and unique items in a gift basket that speaks self-care.

I spy a lot of useful and unique items in a gift basket that speaks self-care.

Lancaster is giving Stoltzfus.

Lancaster is giving Stoltzfus.

Penn Medicine Lancaster General represents at the BIAPA 2022 conference.

Penn Medicine Lancaster General represents at the BIAPA 2022 conference.

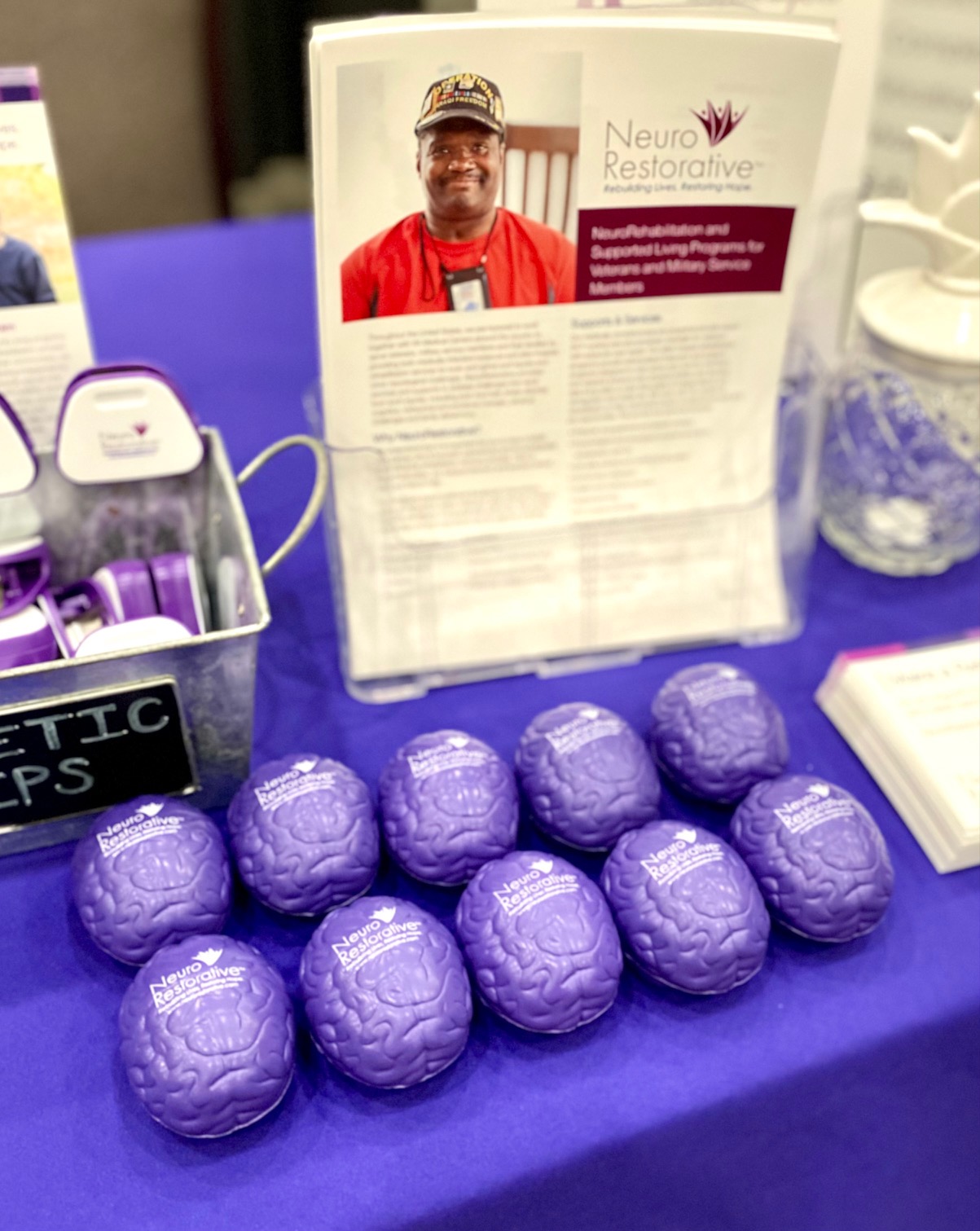

Neuro Restorative gets the word out about its services.

Neuro Restorative gets the word out about its services.

Promotional purple squeeze brains win my Best in Merch vote!

Promotional purple squeeze brains win my Best in Merch vote!

BIAPA’s conference exhibitor table highlights its mission and purpose.

BIAPA’s conference exhibitor table highlights its mission and purpose.

A representative for Main Line Health in Bryn Mawr speaks with an interested conference attendee.

A representative for Main Line Health in Bryn Mawr speaks with an interested conference attendee.

Christabelle Braden is a singer/songwriter and founder of Hope After Head Injury, a brain injury support group.

Christabelle Braden is a singer/songwriter and founder of Hope After Head Injury, a brain injury support group.

Christabelle Braden speaks her truth, giving hope and support to others.

Christabelle Braden speaks her truth, giving hope and support to others.

From Left, Christabelle Braden and Sharon Kozden meet up to chat about the healing power of music.

From Left, Christabelle Braden and Sharon Kozden meet up to chat about the healing power of music.

I spent a lot of time at this table throughout the conference, becoming familiar with Mind Your Brain Foundation‘s work and purpose.

I spent a lot of time at this table throughout the conference, becoming familiar with Mind Your Brain Foundation‘s work and purpose.

Executive Director and Founder of Mind Your Brain Foundation Candace Gantt also is a TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury) survivor.

Executive Director and Founder of Mind Your Brain Foundation Candace Gantt also is a TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury) survivor.

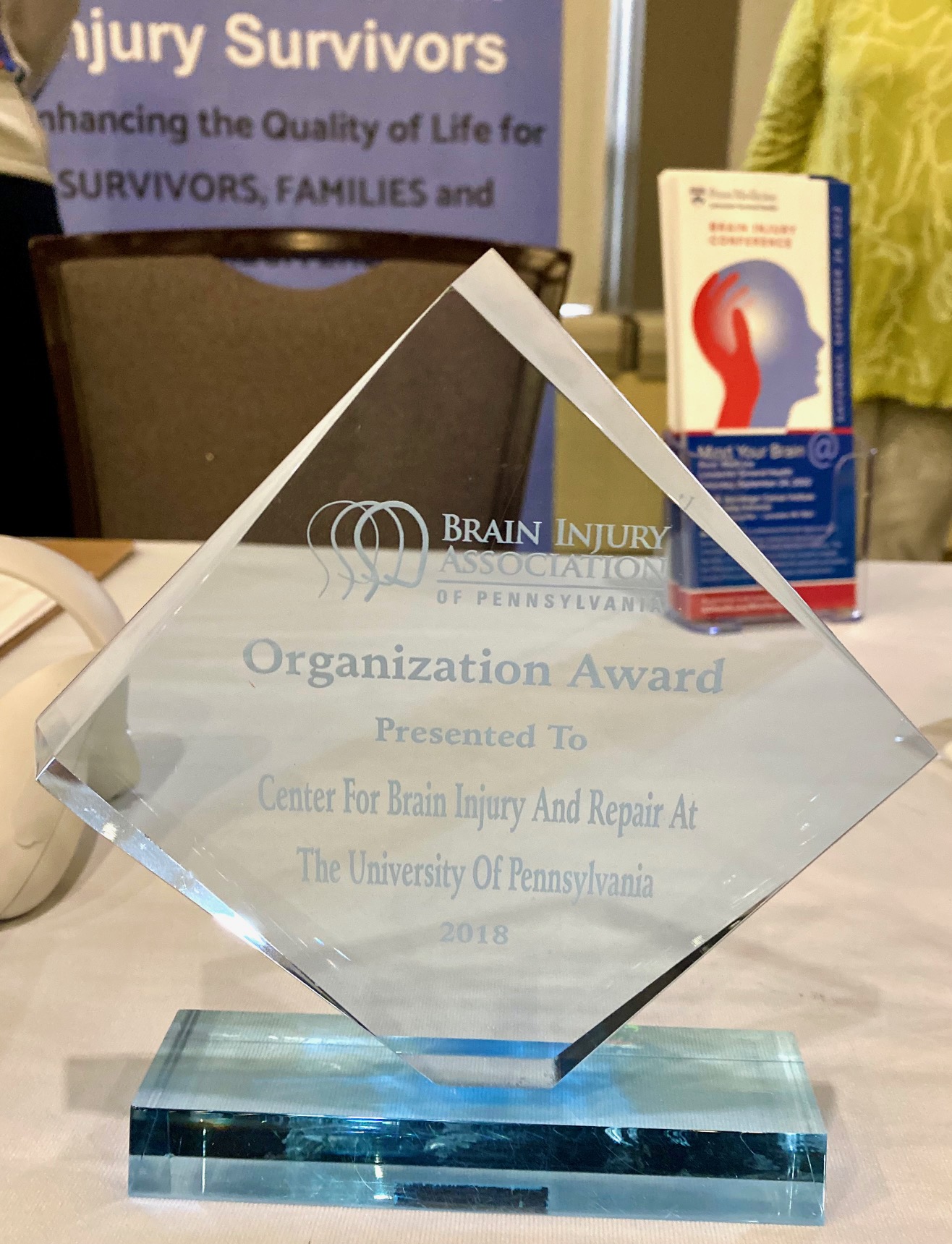

The Penn Center for Brain Injury and Repair (CBIR) employs a multi-disciplined approach in addressing traumatic brain injuries. BIAPA awards CBIR, circa 2018.

The Penn Center for Brain Injury and Repair (CBIR) employs a multi-disciplined approach in addressing traumatic brain injuries. BIAPA awards CBIR, circa 2018.

Grey matter, deconstructed for educational purposes.

Grey matter, deconstructed for educational purposes.

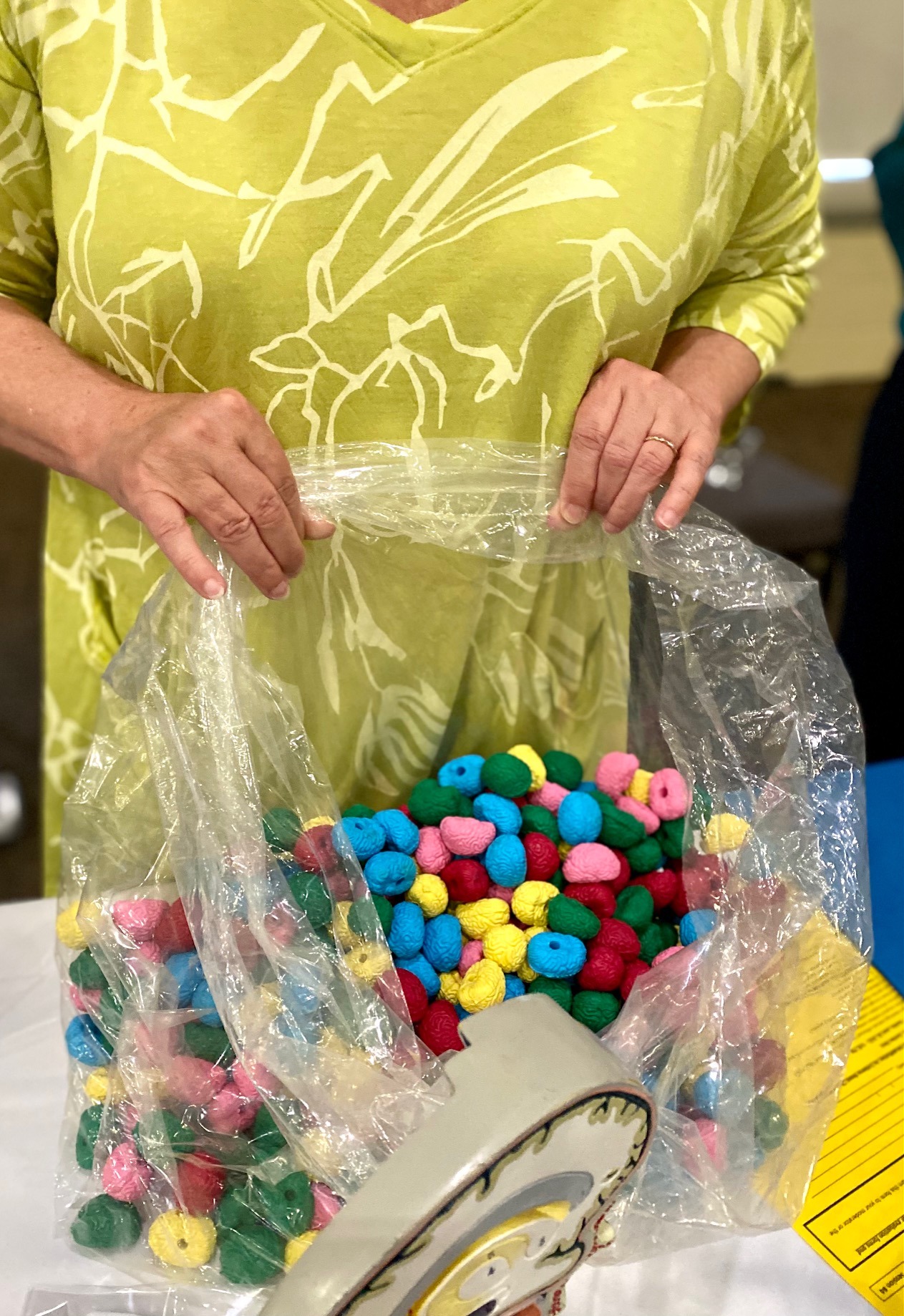

Check out this colorful bag of colorful brain erasers! Fun promotional merch is a definite draw for vendors and exhibitors.

Check out this colorful bag of colorful brain erasers! Fun promotional merch is a definite draw for vendors and exhibitors.

An oculus virtual reality headset features leading edge rehabilitation technology with immersive exercises that “stimulate brain function and help form new neural pathways to aid recovery.”

An oculus virtual reality headset features leading edge rehabilitation technology with immersive exercises that “stimulate brain function and help form new neural pathways to aid recovery.”

It’s a brave new brain world for writer Sharon Kozden.

It’s a brave new brain world for writer Sharon Kozden.

Exhibitor tables are lined up around the main conference room, which awaits attendees and speakers alike for three days of informative and educational sessions and programs.

Exhibitor tables are lined up around the main conference room, which awaits attendees and speakers alike for three days of informative and educational sessions and programs.

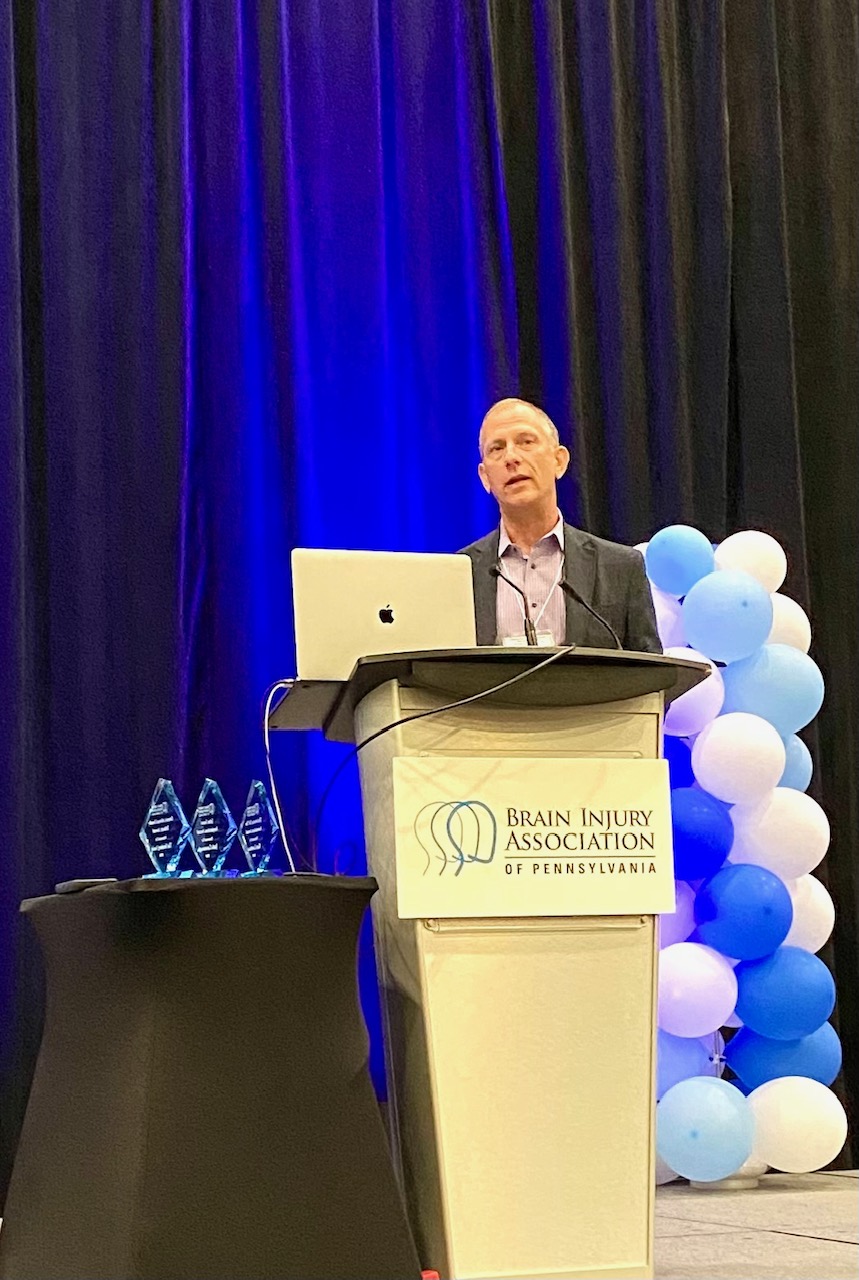

BIAPA’s 2nd VP Damon Slepian serves on the Board of Directors.

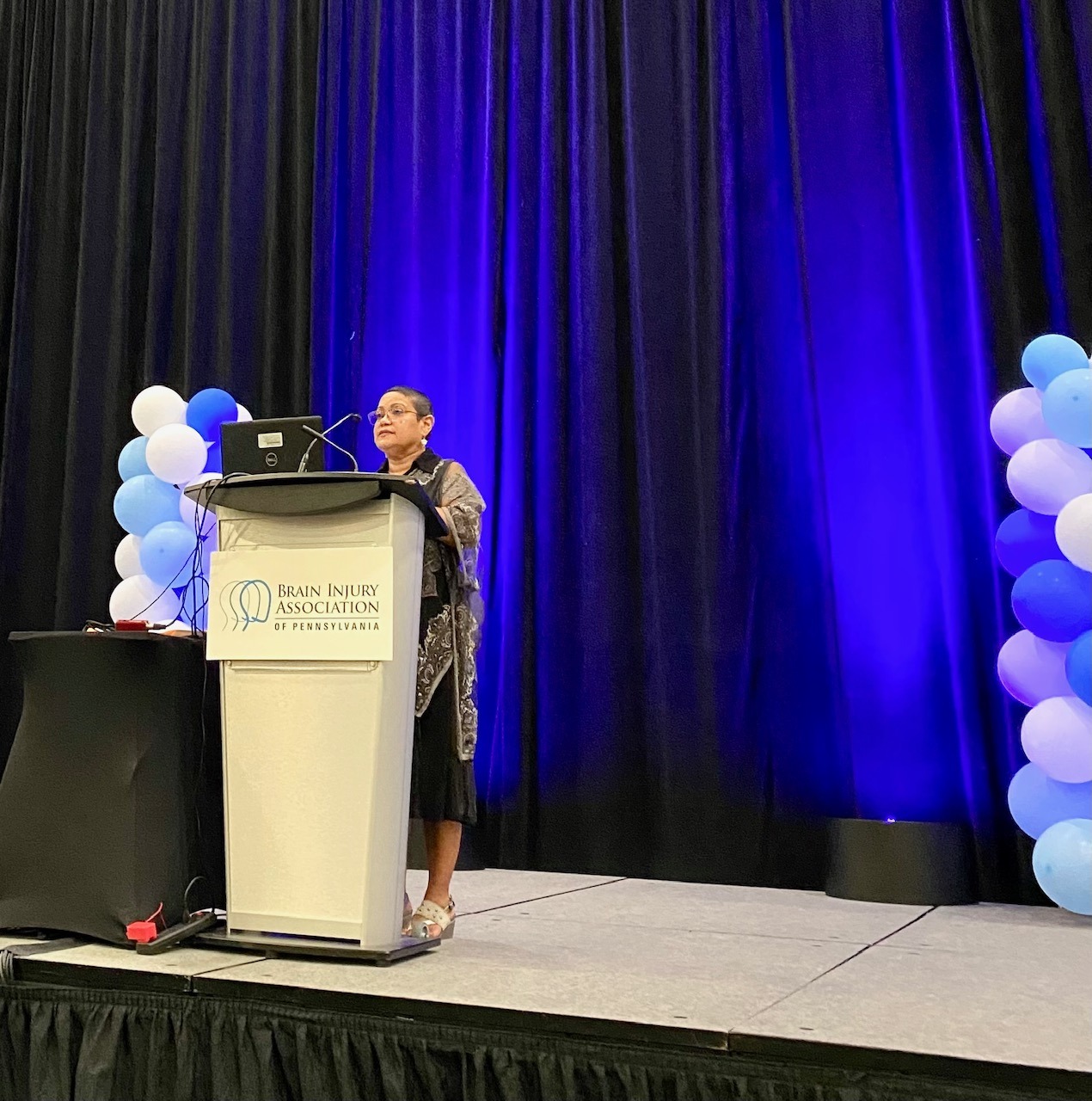

Dr. Lydia Navarro-Walker presents.

Dr. Lydia Navarro-Walker presents.

Conference attendees show up ready, willing and eager to learn from a highly knowledgeable group of presenters.

Conference attendees show up ready, willing and eager to learn from a highly knowledgeable group of presenters.

Miniature vases with beautiful bouquets of fresh flowers graced mealtime tables.

Miniature vases with beautiful bouquets of fresh flowers graced mealtime tables.

Conference attendees and participants enjoyed delicious lunch fare and companionship in between presentations and lectures.

Conference attendees and participants enjoyed delicious lunch fare and companionship in between presentations and lectures.

A plate of hearty fixings was served up with the perfect summertime Lancaster touch.

A plate of hearty fixings was served up with the perfect summertime Lancaster touch.

Ample luscious dessert options were available for the sweet of tooth.

Ample luscious dessert options were available for the sweet of tooth.

Proud dog mama poses with her canine bestie.

Proud dog mama poses with her canine bestie.

While the pandemic nipped in the bud in-person conferences, 2020’s awards were presented better late than never.

While the pandemic nipped in the bud in-person conferences, 2020’s awards were presented better late than never.

Front and center-seated and ready to accept awards.

Front and center-seated and ready to accept awards.

From Left, traumatic brain injury survivor Tyler Pritchard and his mother Barbara honor my request for a pose during conference downtime.

From Left, traumatic brain injury survivor Tyler Pritchard and his mother Barbara honor my request for a pose during conference downtime.

From Left, Direct Service Award Winner Allyson Diane Hamm displays her award with BIAPA President Dr. Ann Marie McLaughlin. Allyson is a front-line staffer at Success Rehabilitation, Inc. (SRI) since 2014 and was honored for providing “exemplary service to individuals with brain injury.”

From Left, Direct Service Award Winner Allyson Diane Hamm displays her award with BIAPA President Dr. Ann Marie McLaughlin. Allyson is a front-line staffer at Success Rehabilitation, Inc. (SRI) since 2014 and was honored for providing “exemplary service to individuals with brain injury.”

From Left, BIAPA’s 3rd VP Dr. Madeline (Maddie) DiPasquale is all smiles with BIAPA President Dr. Ann Marie MacLaughlin as she displays her Dan Keating Pioneer in Brain Injury Award. Named for former BIAPA Board President Dr. Dan Keating, the prestigious award recognizes “an individual whose initiative, expertise, and creativity have led to the development of services and supports in the field of brain injury rehabilitation.”

From Left, Dr. Eileen Fitzpatrick-DeSalme with husband Rob DeSalme. Dr. Fitzpatrick-DeSalme is a “clinical neuropsychologist who has spent over 30 years devoted to the clinical care of people with brain injuries at MossRehab’s Drucker Brain Injury Center.”

From Left, Dr. Eileen Fitzpatrick-DeSalme with husband Rob DeSalme. Dr. Fitzpatrick-DeSalme is a “clinical neuropsychologist who has spent over 30 years devoted to the clinical care of people with brain injuries at MossRehab’s Drucker Brain Injury Center.”

From Left, Jack Kavanaugh and BIAPA Board Treasurer Anne Sears are pictured with Jack’s award.

From Left, Jack Kavanaugh and BIAPA Board Treasurer Anne Sears are pictured with Jack’s award.

From Left, Jack Kavanaugh and his mother beam with pride.

From Left, Jack Kavanaugh and his mother beam with pride.

A platter of crudites looks invitingly fresh and healthful.

Salad, flavorful roasted vegetables and tender fingerling potatoes are a summertime dinner buffet’s perfect blend of sides.

Salad, flavorful roasted vegetables and tender fingerling potatoes are a summertime dinner buffet’s perfect blend of sides.

On a hot June weekend, an ice cream bar was the perfect choice for the conference’s closing dessert.

On a hot June weekend, an ice cream bar was the perfect choice for the conference’s closing dessert.

Ice-cream toppings entice with a delish blend of sweet and salty.

Ice-cream toppings entice with a delish blend of sweet and salty.

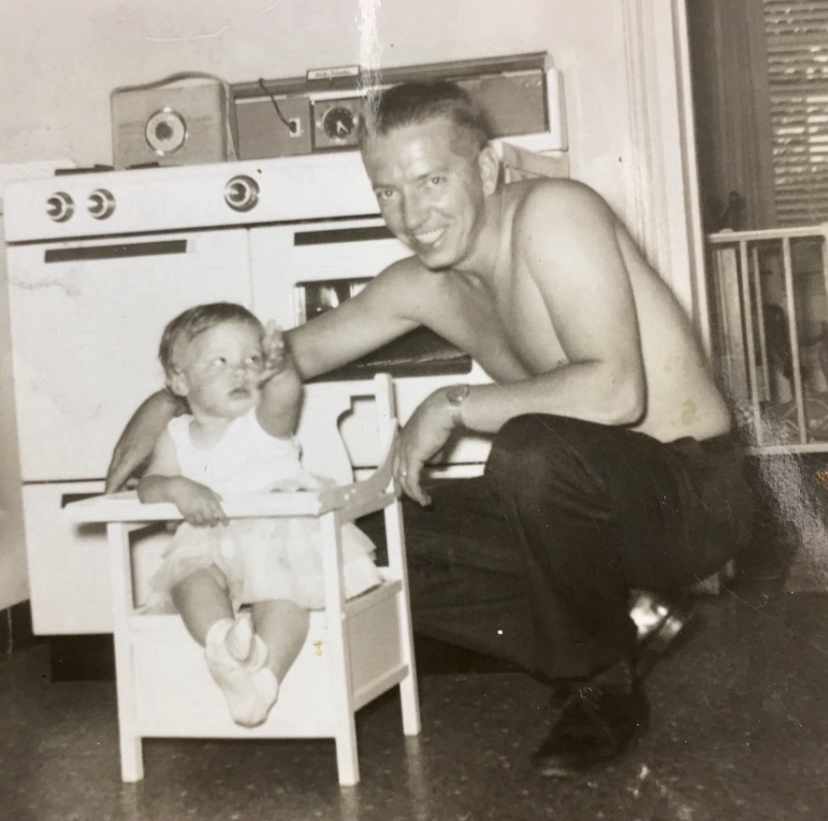

Writer Sharon Kozden and her father–back in the day.

From left, Andrew Anthony Kozden and Sharon Kozden are pictured at Allentown, Pennsylvania’s Phoebe Home during an Eastertime visit.

From left, Andrew Anthony Kozden and Sharon Kozden are pictured at Allentown, Pennsylvania’s Phoebe Home during an Eastertime visit.